Damien Hirst. For the love of God (2007) in publications, exhibitions

Meet Damien Hirst’s long-lost "art grandmother", performing sensational diamond publicity back in 1940, before her celebrity "It Girl" media coverage implosion. Her name is Emily. Plus a list of exhibitions and selected publications regarding For the love of God, (2007).

artdesigncafé - art | Art Design Publicity (Remix) | 12 September 2021 | Updated 11 January 2024

OVERVIEW OF SECTIONS

A. Meet the lady wearing millions in diamonds back in 1940 (essay)

B. Why I love Damien’s skull [: The international media / communications results are just too good] (essay in Sculpture magazine)

C. Damien Hirst’s skull at the Rijksmuseum (essay in Sculpture magazine; "behind the scenes" disclosure)

D. Exhibitions and varied publications of Hirst’s diamond skull

A. MEET THE LADY WEARING MILLIONS IN DIAMONDS BACK IN 1940

Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe Diptych collaborator, Emily Hall Tremaine, as publicity predecessor of Damien Hirst’s diamond skull

by Robert Preece

Emily & Sensation | Hirst’s £50m diamond skull | Emin’s My Bed

Emily & Three Flags | A Boy for Meg | Marilyn Diptych | Victory Boogie Woogie

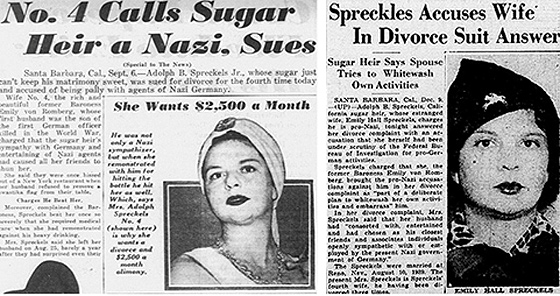

Date: 6 September 1940. See: Emily Hall Tremaine - crazy anti-Nazi media coverage.

Date: 10 December 1940

Context: Mother of the famous Victory boogie woogie by Mondrian in the Hague, Warhol’s Marilyn diptych at the Tate, and Johns’s Three flags, Emily Hall Tremaine (previously Spreckels) accused her dodgy second husband of being pro-Nazi in divorce court. After 4 full-on national media coverage cycles in the US, he fired back with more media Sensation, "I’m not the Nazi, SHE is". This was in posh California.

Sample clip, front page, at top, Altoona, Pennsylvania: photo / caption with Emily: "Charged with Naziism". The photo is re-used from an earlier publicity cycle in which Emily wore over $1 million in diamonds (maybe 14.5-220m today, walking with two guards) and stole the press away from the posh guests at the costume party. (Emily is thought to have been an "eyes and ears" spy in the social set for US military intelligence.)

Art historical interpretation: "Here Emily fused the sensibility of both Damien Hirst with his flash diamond skull, but became the diamond skull herself. This was combined with Tracey Emin-like shock, first with shocking disclosure, and as we see, tabloidesque scandal." (R. J. Preece)

Read more

|

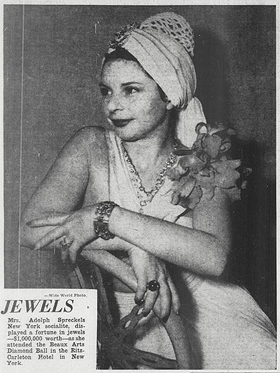

LEFT: Wire service photo of (pre-Warhol) Emily Spreckels (later Tremaine) wearing in today’s value from USD$14.5-220m in diamonds and stealing the press at the Beaux Arts Ball in New York, partly a piss-take and signalling her move up the society ladder (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 30 January 1940, p. 22). Deeply buried in art and design history, Emily’s event and media performance, with presumably rented diamonds, were reported nationally across the United States. Sixty-seven years later, Damien Hirst and his team adopted a remarkably similar visual and communications strategy with the presentation of his diamond skull (2007). Note the two large diamonds placed on both foreheads. However, in 2007(+), international media structures were activated within a developing story construct and the diamond skull reappearing on tour. |

Given the buried nature of the work and life of Emily (1908-87) before 1960, and especially before 1944 when she turned intensively to art and design show organizing and collecting, this can be assumed to be new historical information put forth to almost everyone. When one looks more closely into Emily’s buried history, one also finds more surprises of a very sensational, and sometimes shocking, nature.

Sample media coverage from the 1940-41 divorce case, Emily vs. Adolph B. Spreckels, Jr., that shocked the United States for 4-6 months with a multiple news cycle. It is thought that Emily, a self-made publicity master, pursued this— battling Nazi support in elements of American high society and business— not only against Adolph, but his wider sphere, in consultation with Ellis M. Zacharias, head of US Pacific area naval intelligence. After WWII, Emily turned her attention to contemporary art as an organizer and collector. Her acquisitions included the purchases of several early works by Warhol, who may have been aware of Emily and this "I’m not the Nazi, YOU are the Nazi" scandal.

Later in September 1940, Emily courageously stood up and publicly blasted her second husband after a turbulent year-long marriage: "no" to his alleged extreme spousal violence and "no" to his alleged pro-Nazism. This was reported, via her initial divorce filing, in probably all media markets across the United States via wire service reports. Then it got messy.

> To learn more, and see more photos of shocking media coverage, see Meet the other lady behind the diptych; The depiction of the Marilyn Diptych as autobiographical for Emily Hall Tremaine. [Scroll down to the article concerning a (to date) unknown context of the voted #3 most influential work of Modern art. Emily advised Warhol put the two panels together— showing celebrity and destruction, which she also experienced.] (R. J. Preece, artdesigncafe.com; Contributing Editor, Sculpture magazine, 16 September 2021; updated 18 September 2021.)

R. J. Preece in the author of the forthcoming book Nazis in California: The dangerous journey of Emily Spreckels in high society, 1933-45 | Was she a California Nazi, a US patriot-spy, or was she both? (2025).

For more information, see Section I. Mystery, danger & misunderstandings: Emily Hall Tremaine in the 1930s on the Emily Hall Tremaine / Collection compilations and documentation overview page.

B.1. Why I love Damien’s skull [: The international media / communications results are just too good] (essay) (2008)This article was previously published in Sculpture, 27(1), January / February 2008, pp. 42-5. A diamond-encrusted skull…worth £50m (US $100m)…said to be the most expensive piece of contemporary art…entirely covered in 8,601 jewels… skull of a 35-year-old man from the 18th century…new teeth were made… at a cost of £14m (US $28m)…“It works much better than I imagined. I was slightly worried that we’d end up with an Ali G ring…I wouldn’t mind if it happened to my skull after my death.”

Read more Perhaps I’ve confused some readers with this introduction. So, let me start out by stating: I love Damien Hirst’s skull, otherwise titled For the love of God (2007). Why, you might be asking? Because this work designed by Hirst and his team brilliantly fuses the media / communications potential of an artwork with its artistic expression. And with the skull’s complementary contexts, this media / communications combo (the artwork and its language) propelled its reach far beyond the art world, securing it a wider range of media coverage, even to the point of hitting the headlines in several countries. For the love of God, and the furor surrounding it, also crossed language barriers with incredible speed and efficacy. My jaw dropped the day I saw the skull and the reported sale on my msn.nl start-up screen— in Dutch. I wish I had set up a daily alert on Google to record the rise in Google hits across the world’s top 25 languages, to watch this snowballing media and Internet discourse in full multilingual action. In a strand of my previous writings, I’ve focused on the artwork, its embedded language, and its embedded media / communications power. I’ve referred to the power of visual elements and the principles of design, effective copywriting, and press relations— within the context of critical media analysis. This work has included analyses of media-savvy designer Philippe Starck and artists Marc Quinn and Tracey Emin— plus a rare interview, my favorite actually, with the creative mind behind Press Relations and Publications at White Cube gallery.[1] What strikes me about the skull is its giant stride forward in media coverage— bejeweled, bizarre, and bewitching— and what lurks at the heart of this interest— price. Pounds, dollars— “most expensive ever,” our dear skull has demonstrated new opportunities in international cross-media coverage for contemporary artworks. This impact, and the context of the work, shows the power of media / communications strategies when embedded in a work and combined with visual art language and expression. The synergy makes one question to what extent combined media strategies (mass media and visual media) are driving some artistic practices and ask if what is surfacing is like a staged art intervention. The extent to which this can be characterized as performative art is contentious and up for debate.[2] Anyone who takes media/communications opportunities seriously cannot be unimpressed, especially when one considers the size of the team that probably produced the results. At the end of the day, this impressive achievement probably occurred on a relatively minimal budget for press planning and relations (when compared to the outlays of much larger organizations). It was no surprise when the artwork-artist-gallery-celebrity combo spilled into art, lifestyle, and entertainment / celebrity magazines and newspaper sections— such a development was somewhat predictable after the media/ communications design benchmarks of Philippe Starck hotel projects a decade earlier.[3] But with the skull, the price appeared to drive almost all of the coverage. Consider the following searches: [“Damien Hirst” +“skull” +“50m”] (circa 755 Google hits); +“100m” (416 hits); +“50 million” (746 hits); +“100 million” (575 hits); +“million” (45,300 hits); +“millions” (10,900 hits); +“pounds” (10,400 hits); and +“dollars” (13,500 hits). A search on “most expensive” pulls up about 11,100 hits led by The Guardian, the New York Times, BBC News, the International Herald Tribune, and the powerful new medium, Wikipedia. When you subtract all of these price-oriented terms and phrases, the Google count plummets from 108,000 to just 494 hits. This price-led dependence, recalling large sales figures trotted out by auction houses, helps to account for the skull’s magnetism in international business and news media, something that would have been nearly impossible before today’s highspeed information flows. In, say 1998, a few hundred press results would have impressed, and it would have been very time-consuming to collect good samples and estimates. Now, however, the stakes have reached a new level with tens of thousands of easily searchable possibilities that give a kind of overview. Just go to Google, enter your search terms, click, and search for yourself. Other interesting things pop up when you examine the coverage. For example, [“Damien Hirst” +“skull” +“diamond”] racks up about 61,600 hits, including Artnews and [anthropology.net], as well as ABC news in the U.S. Switch to “diamonds,” and the first 20 hits include the Daily Mail, [bloomberg.com], and Reuters, as well as White Cube. [“Damien Hirst” +“skull” +“It works much better than I imagined”] (circa 158 hits); +“I was slightly worried that we’d end up with an Ali G ring” (circa 91 hits); and +“I wouldn’t mind if it happened to my skull after my death” (circa 117 hits) show samples of quote delivery and media result multiplication. Here, the results are not so impressive. But then try +“George Michael” (the singer was reportedly interested in making an offer on the skull), and about 13,300 hits appear: a clear expansion into celebrity, music, and, once again, general news outlets. Another interesting search concerns the language of the work as presented on the gallery Web site: “explor[ing] the fundamental themes of human existence— life, death, love, immortality and art itself.”[4] I searched the second part of the sentence, and only five hits emerged, then switched to [“Damien Hirst” +life +death +truth +love +immortality], drawing an unimpressive 389 hits. Why this disconnect between the numerous appearances of sensational phrasing and the paltry showing of more elevated themes? Are the vast majority of the world’s print and Web editors unimpressed, or unexcited, by drier, thematic language? And how do we make sense of the dissociation between more specialist art classification (top-down approach) and non-specialist language that uses phrasing drawn from the fundamentals of art language (visual elements, principles, materials, context)? For me, writings that do not account for the media/communications power, in other words, the “sex, drugs and rock n’ roll”[5] of For the love of God and works like it have bypassed the visual experience[6] of the piece to engage in a more elevated discourse removed from the art. Elevating language above elements, principles, materials, and contexts does not account for the work’s mass media power or media / communications orientation. A combined analysis based on the fundamentals of artistic construction, paralleled with those of media / communications is the only way to account for such widespread cross-media coverage, with all but George Michael built directly into the art product. The skull demonstrates the effectiveness of sensation-based media / communications art. Honey Luard, White Cube’s head of Press Relations and Publications, believes that both aspects can co-exist in and around the same artwork, without the hype tarnishing the art. In 2002, she told me, “If a certain amount of hype means that it happens, means that all the resources available are marshaled together to make it happen, even if it goes out in a huge fanfare with lots of flashing lights— like some of the White Cube openings with the paparazzi waiting outside. People criticize it for all of the perceived hype, but all of that does fall away, and does so very quickly. What you’re left with— you hope— [is] some very good art, and some decent writing. This can then be built upon.”[7] No love is perfect, including my love for Damien’s skull. While the media coverage maximization represents a sort of benchmark at this time, and it appears to fit the objectives of the stakeholders, what about competing artists and galleries? While it can be argued that the more attention paid to contemporary art is a positive step, will this approach crowd out others as brand-naming gains more power? We’ve seen this with the English language, with local/national musicians, filmmakers, and TV producers being crowded out by their more high-profile, often American, competitors. Will the result be that more media-savvy artworks, artist practices, and teams gain a comparable, greater share of the market? Only time will tell, but I should mention that the £50m skull, like its media discourse, has multiplied. Five silkscreen print editions are on offer, all available through Hirst’s Web site [othercriteria.com]. Three in editions of 250, at £10,000 each. One edition of 750 at £5,000 each. And another of 1,700 at £900— each (prices do not include Value Added Tax; estimated shipping time: eight weeks). R. J. Preece References: [2] Clearly the precedents here include Andy Warhol, Chris Burden, Jeff Koons, and Mark Kostabi, with parallels to Tracey Emin and Spencer Tunick. [3] My MA thesis examined 100 published press results of a Philippe Starck-designed hotel on Miami Beach. [4] Search done on October 1, 2007. [5] This is a boiled-down description offered by Patricia Ellis. (See interview below.) [6] See Robert Storr’s comments in the 2007 Venice Biennial catalogue, volume I, p. 18. Storr directs viewers to look at the sensation-rich elements of the work of El Anatsui as a starting point, with reference to an excerpt of my published interview with the artist in Sculpture, vis-à-vis more art historically contextualized readings, which in this instance, he finds problematic. [7] Honey Luard, quoted in “Behind the Scenes: Now It’s Honey’s Turn,” op. cit., p. 24. B.2. Damien Hirst: Hype buzz, glamour and art - Interview with Patricia Ellis (2008)This article was previously published in Sculpture magazine, 27(1), pp. 44-5, January / February 2008. It was published in a side box to the feature on Damien Hirst’s skull, above. While preparing the article "Why I love Damien Hirst’s skull" (above), R. J. Preece contacted Patricia Ellis to inform her— and ask approval— about the footnotes mentioning her words and actions. This prompted a discussion dealing with art and media coverage in relation to Damien Hirst’s skull... Read more He wanted to share this discussion, which would normally be a behind-the-scenes conversation, with Sculpture readers (with her approval). Ellis is a freelance art writer (she has written essays for several well-known institutions including the Saatchi Gallery), curator, and artist in London. She was the editor of Make and a former news editor of Flash Art and has occasionally appeared on international broadcasts, including the BBC. [...] R. J. Preece: I’m seeing a disconnect between the way art is elevated in language and the sensational phrasing that is multiplying the, at least, non-art-centered coverage. What do you think of this? Patricia Ellis: I think it’s just that art engages with different audiences in different ways. You’ve got the “professional audience” and the “public audience”— the people who come to art through its coverage in mainstream media. I think that there has always been a bit of a disconnect. If you ask Joe Public about Van Gogh, for example, he’s “the guy without the ear”; maybe they know his Sunflowers. I think often the general public only become acquainted with art when there is hype and buzz. R. J. Preece: So are we saying that art people, while they recognize and are perhaps moved by the highly sensational elements, prefer to use this elevated language to describe it? Patricia Ellis: To a certain extent. I think that many “professionals” love the sensationalism, as it opens up new dialogues for approaching art criticism. A lot of writing from 20 or 30 years ago was very theoretical, critical, and quite dry. Along with the emergence of the YBAs, and increased mass media coverage of art, critical writing has in many cases become more performative, clever, and innovative in its strategies. It’s more accessible. But you still have a lot of “academic” writing as well. Damien Hirst’s skull piece is incredibly glamorous and sensational: real skull, real diamonds— it’s obscene opulence and indulgence. In many ways, this is the critical context of the work— the critical dialogue exists within the sensationalist hype of the piece. For me, the iconography of the piece isn’t so interesting— the bling disco death-head thing has been done before in more impoverished variations. The interesting thing is the brazen fetishization and attitude— Hirst’s done it for real, using real diamonds, real cash. R. J. Preece: Do you think that the rather effective media/communications elements are within the work? Patricia Ellis: The skull piece was most likely anticipated to create a huge interest through a wide variety of media. I’m sure that Hirst did not make the piece and then go, “Oh my God! I can’t believe I’m on television in America.” But I think these elements are actually part of the life, death, (im)mortality concepts of Damien Hirst’s work. If you look at how media operates it’s very much about temporality, multiplication, and the sublime. Hirst is not so dissimilar from Andy Warhol. He is a global brand. I don’t think you can separate it. I think it is definitely part of the concept of his work. R. J. Preece: So in essence, you agree with what I’ve been going on about. Patricia Ellis: I think that all artists are hyper-aware of how their work is transacted and received. Visual art has its own language. You make things using that language to articulate an idea, direct its interpretation. It’s entirely possible to appropriate the media structures surrounding the work as part of that statement. R. J. Preece: But the art press is not having this kind of discussion? Patricia Ellis: The art press isn’t really interested in how many Google hits Damien Hirst got— or why. It addresses a relatively small audience, like any publication written by and for “professionals.” It’s a small world: you’re often reading about people you actually know. Art press doesn’t usually discuss how art is situated in the mainstream, basically because everyone is very familiar with and has their own understanding of how this works. Art media acts as a forum for a much more in-depth investigation into the concerns of contemporary practice. Its concerns are very distinct from media hype. It may be “elevated” as you suggest, but if it wasn’t we’d simply only appreciate art for its shock, financial, or social worthiness value. So “yes” to elevation— the higher the better! R. J. Preece: So would you interpret Hirst as playing this at both an art world level and a more mainstream level? And is this central to his work? Patricia Ellis: Yes, of course, in a very sophisticated way. |

C.1. Damien Hirst’s skull at the Rijksmuseum (essay)This article was previously published in Sculpture magazine, March 2009, pp. 14-5, with the title "Rock star on tour: Damien Hirst’s skull at the Rijksmuseum".

damien hirst rijksmuseum amsterdam

For just over a month (November 1 - December 15, 2008), Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum acquired a new art chapel, an almost pitch-black, 30-square-meter room housing Damien Hirst’s spotlighted skull, For the Love of God (2007). I entered the space after taking part in what was almost a procession. Accompanying me on my sneak peek were a German and a Belgian journalist, the museum’s general director, a curator of 17th-century art, a recent hire for contemporary interventions, and a museum press officer. We walked through rooms filled with old masters, the three writers carrying contemporary attributes— glossy black shopping bags with large diamond skulls imposed on them and filled with press kits, catalogues, and photo CDs. Read more Tension between art, marketing, and celebrity defined this installation of the diamond skull and the accompanying exhibition of 17th-century art guest-curated by Damien Hirst. [1] The same tension may also explain why Hirst’s work is difficult to place. It seems to touch early 21st-century life in global capitalism: installed with intense Caravaggesque lighting beamed strategically from above, the entire package was designed to dazzle as well as repulse. But most of all, it was designed to get people talking. ’I am not concerned about

the details of these sales. What matters to me is that they were announced— unleashed, picked up, printed, reprinted, accelerated, translated, and multiplied across global media. But beneath the surface text, intense darkness remains.’ — R.J. Preece What’s particularly impressive about For the Love of God, and its accompanying exhibition, is how it generates a wide range of strong reactions— and how it seems to marshal so many key issues and strategies, with impressive quantitative results. This success is arguably led by the skull’s sensational form, costly materials, and price on the one hand, and its themes—both intellectual and emotional—such as greed, death, and immortality on the other. Its placement inside a prestigious and historical European art collection not only added a new context for the work to generate discussions about meaning, it also acted as an additional media / communications power-layer and talking point. At the same time, we see brand strengthening not only for the skull, the new rock star, but also for Damien Hirst, the art star, as well as for the Rijksmuseum. At first, I found For the Love of God a bit like an over-the-top freak-object, a disco death-head, almost camp. Are all of these diamonds real? But what struck me was that the skull appears smaller and more fragile than its confident appearance in photographs and on television. This draws an important distinction between original and mass-media re-presentation in relation to discussions on celebrities. Set inside a glass case, this precious item of highly exclusive global privilege also became a public object for visitors who paid to enter the chapel for the unique experience and entertainment. Questioning many things about money, celebrity, cult of personality, and mass media, the work looks like a twisted, isolated, painful trap. Is this what Damien Hirst has learned on his remarkable journey? How symbolic and how personal is this object? The skull perhaps radiates a certain truth of our time, magnified by the extreme cost of the materials (reportedly £12 million) and its equally extreme sale price (£50 million), pushed by increasingly networked capitalist and global hierarchies—and with them, the international art hierarchy. The packaging of the object, however, may be deceptive. Like today’s vulnerable corporations, a skull with 8,601 flawless diamonds appears in principle to run the risk of being dismantled for higher profit— especially the branded Skull Star Diamond placed in the forehead. In any event, the material itself is also an investment. After a few minutes of our group’s viewing, low light filled the space and unexpectedly revealed two security guards standing against the walls. I was reminded of the darkness in Rembrandt’s Night Watch (1642), on view next to Damien Hirst’s curated exhibition. The details of the skull’s current ownership likewise remain in darkness after the dramatic media coverage of its sale. [2] And just six weeks before the opening of the Rijksmuseum installation, it was announced internationally and extensively that an auction of Damien Hirst’s work raised £95.7 million from the sale of 223 lots at Sotheby’s in London. I am not concerned about the details of these sales. What matters to me is that they were announced— unleashed, picked up, printed, reprinted, accelerated, translated, and multiplied across global media. But beneath the surface text, intense darkness remains. Stepping out into the artificial light of the museum and back among the public, I entered the accompanying exhibition of 16 paintings from the Rijksmuseum collection selected by Damien Hirst. I was struck by how he was allowed to achieve a traditional desire of the artist— contextualization into Art History. In addition, the show demonstrated an innovative, effective approach to historical and contemporary art partnerships, artist brand-building, and rock star recognition. The 16 paintings were divided into five sections. Most important were those drawing connections to the skull and themes of mortality; [then] a group of [four] morality paintings showing life’s choices; a political commentary and a landscape; a bizarre triptych consisting of still-life imagery. Four works related to a [fifth] section of public/private [personae, by a still-life] showing a keen eye for detail, a depiction of the expulsion from Eden, and a 17th-century bacchanal scene, [which itself referred to an earlier time period, the Greco-Roman.] A standard museum produced label was located next to each work, and Damien Hirst offered his take— in Dutch and English.

Damien Hirst & the diamond skull at the Rijksmuseum, exterior promotional image, 2008-09.

Drawing a connection between the skull, as well as life and inevitable death, Damien Hirst included Hendrick Bloemaert’s Woman selling eggs (1632), commenting, "A great image. The beginning and the end. I love the way the egg makes us think of a skull although her skull is protected by the scarves." One of my favorite selections was Satire on the Trial of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (1663). Hirst comments: "Heaven or hell? You decide. It seems like too many magic mushrooms to me. He’s definitely gone too far down one of those roads, too far to turn back. I feel sorry for him but then part of me thinks he’s having some kind of fun." At this point, I started to question the cheeky, mediagenic, populist quotations. Here, a dual discourse— art specialist and populist-sensational— was presented. I was struck by how much Damien Hirst sounded like some BFA students commenting on historical works. I was also reminded how this used to irritate my art history lecturers. Is this what Hirst really thinks, or are these quotations supposed to represent what the public persona of Damien Hirst should say? Parallel media campaign: Marc Quinn - Kate Moss - solid gold A somewhat parallel visual and verbal exhibition-campaign was taking place at the same time at the British Museum, where Siren, Marc Quinn’s reportedly solid gold sculpture depicting supermodel Kate Moss, appeared as part of Statuephilia. As with Damien Hirst’s diamonds, the material for the sensational 50-kilogram statue—reported to be worth £1.5 million— could conceivably be "deconstructed" for its own value, in this case melted down. Marc Quinn’s work could end up as some sort of saleable multiple with the added value of the material originally being part of a famous artwork on view in the prestigious British Museum. In both cases, the objects achieve new sensation levels and public attention based on apparent extravagance as opposed to possible material investment with added art publicity value. Marc Quinn opts for celebrity subject matter with a borderline shocking pose. This provides five visual and verbal media / communications layers to the work: the material, the cost of material, the celebrity subject matter, the sensational yoga pose, and the prestigious and potentially discussion-generating siting. There’s a sixth point too, stated in the press release: "Quinn’s work is the largest gold statue since Ancient Egypt." In the museum, the work was juxtaposed with classical statuary. The British Museum received comparable benefits to those enjoyed by the Rijksmuseum, benefits that extended to sponsors and museum partners. In addition, "Kate Moss" is a language device that enables movement into the fashion and lifestyle trade presses. It’s all visible via a Google search. For the art press, it’s arguably more effective to communicate the specialized language of the visual art outside of its marketing and mass-media contexts. These two artworks demonstrate an innovative new kind of visual and verbal communications strategy, showing the building of icons and brands by artists and their teams. But the rock star and Damien Hirst, building on the work of their art star predecessors, create a real challenge. Maybe art writing and art history need to connect more with the frameworks offered and developed in other disciplines, at least when art, marketing, and celebrity begin to intersect. Here, the music industry, brand-building, mass-media research, defining target groups, and evaluating public relations campaigns all seem relevant. Looking back into history, we know that some artworks end up marshalling crucially diverse elements and representing their time. For the Love of God may indeed be the artwork of our time. Love it. Hate it. Be bored by it. These reactions don’t seem to matter. In the meantime, visitors kept lining up to visit and pay homage to that skull in the dark room. The controversy and discussions continue. The media reports multiply. And the brand continues to build more recognition. I’m convinced that this event could serve as a case study for other fields in mass media, public relations, marketing, and business contexts. Specializations enable great developments and insights. But they run the risk of becoming so narrow that they lose the larger picture. Of course, Damien Hirst’s project is designed in part to offend— that’s partly what it’s about. But in the end, it’s a very generous gift with a great deal of knowledge. It’s also an Orwellian warning, demonstrating how so many of us globally can be activated, at the cost of almost nothing. References: C.2. Damien Hirst’s skull at the Rijksmuseum: Behind the scenes (2008)R. J. Preece | Art Design Publicity at ADC | 1 June 2009 On 30 October I was invited to preview Damien Hirst’s installation of the diamond skull and an accompanying exhibition of 17th century art curated by Hirst at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum. I saw this work shortly after a special meeting a day before the press conference... Read more Those in attendance included myself, Rijksmuseum director Wim Pijbes, the 20th / 21st century curator, the 17th century Dutch art curator, a press officer and Belgian and German journalists. After a lengthy overview presentation about the visual art and proposed context by the Rijks staff, a Q&A developed focusing exclusively on why we were there: because of marketing, media relations and journalism. Here are some excerpts of the conversation:

Damien Hirst’s diamond skull at the Rijksmuseum: Act IGerman journalist: Would you be willing to tell us how much Mr. Hirst charged? Pijbes: Nothing. There were costs of course to put up the exhibition… German journalist: So, no honorarium for the artist…

Damien Hirst’s diamond skull at the Rijksmuseum: Act IIBelgian journalist: Who owns the skull? Pijbes: We’re not allowed to [say]… it’s normal museum practice. When objects are in private hands, [we do] not disclose the owner. Belgian journalist: I trust you won’t say it, and I trust everything said here has been completely true, but… it’s very marketing-like actually. He just sold [works] for millions at Sotheby’s. This is a beautiful… stunt. That’s why I think the question of the owner is important. Pijbes: Like most museums, we loan a lot of artworks every year. Of course, there’s always this aspect that if a high prestige museum puts a work in an exhibition, and makes a catalogue, that people will come. It will push the value of the work of art. That’s the system. When you write about it, the same happens. German journalist: Whatever we write. [Nervous laughter occurred around the table.] Pijbes: But this [installation] is in a category in itself. It doesn’t make any difference if the Rijksmuseum put this on view or not. It doesn’t add to the value of the work. [Belgian journalist chuckles, sounding in disbelief.]

Damien Hirst’s diamond skull at the Rijksmuseum: Act IIIPreece: Was this decision made easily by the Rijksmuseum? Were there lots of discussions about whether to do this or not? Pijbes: Last year, it was mentioned to the supervisory board, of which I was on prior to becoming the director last July. We all said, "Yes, it was a good idea". Of course, there was discussion, but not controversial discussion. It was a logical thing to put the skull here. The Rijksmuseum is an open-minded institution and looks very closely at what’s going on in society. We’re a 21st century institution with a splendid, award-winning website, with many young visitors, etc. It’s a perfect thing for the Rijksmuseum. Preece: The first stop of this proposed tour is the Netherlands, and we can expect a certain amount of media response from this. There was after all a gaint surge in coverage in London last year. Do you think this is good for [the representation of] the Netherlands in the world? Pijbes: Yes. It will attract people—and gives a new aspect to the image of Rijksmuseum as well. It boosts our image. Of course we do the Old Masters but we are not a "yesterday institution". It’s for now. And Damien Hirst shows this in a very strong way. In this sense, it’s good for Holland, internationally known as an open-minded, small country, with an international focus, and open to new ideas. In this sense, it’s a very Dutch project. Belgian journalist: [An] intentionally quite controversial [project]… |

D.1. Damien Hirst’s For the love of God in exhibitions

This section is in development

| Material status: |

= online = link to more info = completely offline |

| 2000s | 2007 - White Cube, London(3 June - 7 July 2007). Beyond belief at White Cube Hoxton Square and White Cube Mason’s Yard, London. > Exhibition included Damien Hirst’s For the love of God.

2008 - Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam(November 1 - December 15, 2008). For the love of God with separate accompanying exhibition at Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. > Presentation of Damien Hirst’s For the love of God in its own room.

|

| 2010s | 2010-11 - Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy(26 November 2010 - 1 May 2011). For the love of God at Palazzo Vechio, Florence, Italy. > Exhibited Damien Hirst’s diamond skull For the love of God.

2012 - Tate Modern, London(4 April - 24 June 2012). Damien Hirst’s For the love of God at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, London. > Exhibited Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God; in conjunction with Damien Hirst exhibition at Tate Modern (4 April - 9 September 2012).

2013-14 - ALRIWAQ DOHA exhibition space, Doha, Qatar(10 October 2013 - 22 January 2014). Damien Hirst: Relics at ALRIWAQ DOHA exhibition space, Doha, Qatar. > Exhibited Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God.

2015-16 - Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo(16 September - 15 November 2016). Damien Hirst at Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo, Norway. > Exhibited Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God.

|

| 2020s | 2023-24 - Museum of Urban and Contemporary Art (MUCA), Munich(26 October 2023 - 28 January 2024). Damien Hirst: The weight of things at the Museum of Urban and Contemporary Art (MUCA), Munich, Germany. > Exhibited Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God.

|

D.2. Damien Hirst’s For the love of God in publications and related documentation

For rough foreign language translations, see Google translate.

| 2000s | c. 2007 - exhibition webpage - Damien’s diamond skull in White Cube, London exhibition(c. 2007). Exhibition webpage for Beyond belief, an art exhibition of works by Damien Hirst [with mention of the diamond skull, For the love of God]. White Cube gallery, London. (Viewed 17 September 2021. Q00394). 2007 - wire service articlesSee the articles 2007 - spotlighted wire service article, three photos - Damien’s diamond skull on view at White Cube, LondonLovell, Jeremy. (1 June 2007). Hirst covers cast skull in diamonds [with four photos of Damien Hirst’s For the love of God]. Reuters. (Viewed 1 October 2021. Q00570). "’It was very important to put the real teeth back. Like the animals in formaldehyde you have got an actual animal in there. It is not a representation. I wanted it to be real,’ he said..." (Excerpt from above.) 2007 - spotlighted wire service article, photos - Damien’s diamond skull reported to sell for USD$100 millionLovell, Jeremy (London). (30 August 2007). Hirst’s diamond skull sells for $100 million [with two photos of Damien Hirst’s For the love of God, one with Hirst]. Reuters. (Viewed 17 September 2021. Q00390). "A diamond-encrusted platinum skull by artist Damien Hirst has been sold to an investment group for the asking price of $100 million, a spokeswoman for Hirst’s London gallery White Cube said on Thursday... The spokeswoman said she could give no more details of the buyer..." (Excerpt from above.) 2007 - spotlighted article - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonKennedy, Maev. (1 June 2007). Hirst’s skull makes dazzling debut; Damien Hirst was worried his diamond-encrusted skull would look like a £50m disco ball— and he was absolutely right [presumably previously with AFP photo showing the diamond skull]. The Guardian newspaper (London). (Viewed 23 September 2021. Q00431). "... The pondlife press had been ordered to assemble... The correspondent from the Times, judged insufficiently respectful in the past, was banned completely... " (Excerpt from above.) 2007 - spotlighted feature article, two photos - Hirst’s diamond skull reported to be sold(30 August 2007). Hirst’s diamond skull raises £50m [with two photos of Hirst’s For the love of God, one with Hirst]. BBC News. (Viewed 26 September 2021. Q00475). "... Some critics dismissed it as tasteless while others saw it as a reflection of celebrity-obsessed culture..." (Excerpt from above.) 2007 - other articlesSee the articles 2007 - feature article - Hirst’s diamond skull to be on view at White Cube, LondonBrooks, Richard. (29 April 2007). Hirst skull on sale for £50m. Sunday Times (London), p. 2. (Viewed 10 October 2021. Q00611). "... It goes on show in early June at White Cube’s new gallery in London’s West End..." (Excerpt from above.)

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull to be on view at White Cube, London(1 May 2007). Skulduggery from Damien? [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Evening Standard newspaper (London), p. 1. (Viewed 10 October 2021. Q00612). "... Hirst’s new piece... is uncannily similar to the work of the South African born sculptor Steven Gergory, whose 2006 exhibition Skulduggery, featured human skulls decorated with beads and lapis lazuli ..." (Excerpt from above.)

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull to be on view at White CubeBrooks, Richard. (6 May 2007). Damien Hirst’s shark [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Sunday Times (London), p. 14. (Viewed 13 October 2021. Q00613). "Damien Hirst stands to gain [GBP] 50m if he flogs the jewelled human skull from his show at White Cube next month..." (Excerpt from above.)

2007 - feature articleLeyden, Fleur (News Corp Australia). (18 May 2007). Shock art with price to match [regarding Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Herald Sun (Melbourne, VIC, Australia), p. 45. (Viewed 13 October 2021. Q00614). "... A sale of the skull for about [AUS]$120 million would put Hirst, 41, on a price level with Pablo Picasso and Gustav Klimt..." (Excerpt from above.)

2007 - feature mention - Hirst’s diamond skull to be on view at White Cube, LondonCosic, Miriam (News Corp Australia). (19 May 2007). Now you’ve just got to have art; Arts editor Miriam Cosic talks to international expert Tim Marlow about the booming art market [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Weekend Australian (Canberra, A. C. T., Australia), p. 27. (Viewed 16 October 2021. Q00615).

2007 - feature article - Hirst’s diamond skull soon on view at White Cube, LondonAspden, Peter. (25 May 2007). "What else can you spend your money on?" [with significant mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. FT.com (Financial Times) (London), p. 1. (Viewed 16 October 2021. Q00616). "... ’Without precedent in the history of art,’ gushes the gallery’s promotional material ..." (Excerpt from above.)

2007 - TV show announcement - Hirst on BBC2(26 May 2007). Friday: Pick of the day ["... Newsnight Review Special with Damien Hirst; BBC2, 11pm; The artist... gives a rare interview to Kirsty Wark, in which he discussed his work and latest creation— potentially the most expensive piece ever made— a cast of a human skull with over 8,000 diamonds"]. Daily Record (Glasgow, Scotland, UK), p. 46. (Viewed 27 October 2021. Q00617).

2007 - TV show announcement - Hirst on BBC2(26 May 2007). Newsnight Review Special with Damien Hirst 11pm; Pick of the day [regarding Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. The Independent newspaper (UK), p. 1. (Viewed 27 October 2021. Q00618).

2007 - TV listings mention(27 May 2007). Friday 1 June; Choices ["11pm BBC2; Kirsty Wark conducts a special extended interview with... Damien Hirst. He talks about his new works, potentially the most expensive piece ever created— a cast of a human skull covered with 8,000 diamonds."] The Independent (UK), p. 1. (Viewed 5 October 2021. Q00619).

2007 - webpage for BBC2 interview of Damien Hirst(1 June 2007). Damien Hirst special [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. BB2 Newsnight Review / BBC News. (Viewed 27 October 2021. Q00814). "On a special edition of Newsnight Review, an in depth exclusive interview with the man who today produced a diamond and platinum skull expected to fetch 50 million pounds... " (Excerpt from above.) 2007 - feature article, photo - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, London(1 June 2007). The GBP50m diamond geezer; Damien Hirst unveils jewel skull, the most expensive art ever created [presumably with photo of the artwork]. Evening Standard (London, UK), p. 1. (Viewed 27 October 2021. Q00621).

2007 - feature article, photo - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, London(1 June 2007). Hirst unveils £50m diamond skull [with photo of For the love of God with Hirst]. BBC News. (Viewed 22 September 2021. Q00426). "Artist Damien Hirst has unveiled a diamond-encrusted human skull worth £50m - said to be the most expensive piece of contemporary art... " (Excerpt from above.) 2007 - feature article - Hirst’s diamond skull on view at White Cube, LondonAspden, Peter. (1 June 2007). GBP50m price tag on diamond-encrusted skull [with mention of Hirst’s For the love of God on view at White Cube, London]. Financial Times (UK) (online). Hard copy version, 2 June 2007, p. 4). (Viewed 4 October 2021. Q00622; Q00822). "... The gallery is expecting thousands of people to come to see the work ..." (Excerpt from above.)

2007 - article - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonHackworth, Nick. (1 June 2007). A brilliant hymn to our times [review of Hirst’s exhibition including his diamond skull, For the love of God; presumably no photo]. Evening Standard newspaper (London, UK), p. 1. (Viewed 27 October 2021. Q00620). "... [The diamond skull] is a work that literally embodies the vast flows of global capital pouring themselves into the world of art, and the cult of the celebrity artist, two trends of which Damien Hirst, happily, finds himself at the convergent point..." (Excerpt from above.)

2007 - feature article, four photosMartin, Arthur. (1 June 2007). Damien Hirst unveils his jewels in the crown, a £50m diamond-studded skull [with four photos of Hirst’s For the love of God, one of them with Hirst]. Daily Mail newspaper. [Printed in hard copy on 2 June 2007.] (Updated 28 October 2021. Q00568; Q00816). 2007 - news brief(2 June 2007). GBP50m skull is sparkler [possibly with photo of Damien Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Daily Record (Glasgow, Scotland, UK), p. 21. (Viewed 9 November 2021. Q00818).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, London(2 June 2007). Damien’s diamonds are skull’s best friend [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God, possibly with photo]. The Gloucestershire Echo (Gloucestershire, England), p. 5. (Viewed 13 December 2021. Q00825).

2007 - news brief(2 June 2007). Death sells [about Damien Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Daily Telegraph (UK), p. 27. (Viewed 21 November 2021. Q00821).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull in White Cube show(2 June 2007). Diamond geezer [regarding Damien Hirst’s For the love of God on view at White Cube, London; presumably with no photo]. The Daily Mirror (UK), p. 35. (Viewed 27 October 2021. Q00817).

2007 - news brief(2 June 2007). Diamond skull; Damien Hirst has unveiled his latest bizarre creation— a GBP50 million diamond encrusted skull [possibly with photo]. Grimsby Telegraph (Grimsby, England), p. 6. (Viewed 13 December 2021. Q00826)

2007 - feature article, photo - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, London(2 June 2007). Rough diamond Hirst polishes up GBP50m skull [presumably with photo of Damien Hirst’s For the love of God]. Birmingham Post (UK), p. 4. (Viewed 27 October 2021. Q00815).

2007 - feature article - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonDorment, Richard. (2 June 2007). Damien Hirst’s GBP50m skull, unveiled yesterday, throws a hand grenade into the decadent world of art collecting [possibly with photo of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Daily Telegraph (London, UK), p. 20. (Viewed 9 November 2021. Q00819). "... If anyone but Hirst had made this curious object, we would be struck by its vulgarity. It looks like the kind of thing Asprey or Harrods might sell to credulous visitors from the oil states with unlimited amounts of money to spend, little taste, and no knowledge of art. I can imagine it gracing the drawing room of some African dictator or Colombian drug baron. But not just anyone made it— Hirst did. Knowing this, we look at it in a different way and realize that in the most brutal, direct way possible. For the Love of God questions something about the morality of art and money..." (Excerpt from above.)

2007 - feature article - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonLovell, Jeremy (Reuters - London). (2 June 2007). $100-million skull unveiled [with mention of Damien Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. The Globe and Mail (Toronto, Canada). (Viewed 13 December 2021. Q00824). "Damien Hirst, former BritArt bad boy whose works infuriate and inspire in equal measure, did it again yesterday ..." (Excerpt from above.)

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonNews Corp Australia. (2 June 2007). $120m headturner [possibly with photo of Damien Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God, on view at White Cube gallery, London]. The Daily Telegraph (Surry Hills, NSW, Australia), p. 21. (Viewed 9 November 2021. Q00820).

2007 - listingWullschlager, Jackie. (2 June 2007). Visual arts: [listing]; "Damien Hirst - Beyond Belief; White Cube, London... What has been beyond belief recently is not only Hirst’s price tags, but his inability to do anything new. A notorious diamond-encrusted skull, on sale at GBP50m, is the showpiece of this exhibition... " Financial Times (London), p. 20. (Viewed 21 November 2021. Q00823).

2007 - article - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonZheng, Yuxing (Associated Press). (2 June 2007). 8,601 diamonds in this platinum head count [with photo of Hirst’s For the love of God]. Orlando Sentinel (Florida), p. A2. (Viewed 27 October 2023. S00169).

2007 - article - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonAgence France-Presse. (4 June 2007). Britain’s avant-garde rips a page from the playbook of American hip hop [with photo of Hirst’s For the love of God]. National Post (Canada), p. AL4. (Viewed 27 October 2023. S00172).

2007 - article - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Associated Press. (4 June 2007). Price will scare you [with photo of diamond skull print presumably held by Damien Hirst]. Kansas City Star, p. A3. (Viewed 27 October 2023. S00170).

2007 - article - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonReuters. (4 June 2007). It’s a gem! Brit bad boy’s skull sparkles [with photo of Hirst above For the love of God]. Calgary Herald, p. 7. (Viewed 27 October 2023. S00171).

2007 - feature articleBoland, Rosita. (9 June 2007). Is this the jewel in the crown of Britart? [With mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Irish Times newspaper. (Viewed 13 December 2021. Q01002). "... British art critics seem to perpetually love Hirst, and this week they have been ransacking their thesaurus to find ever more elevated terms of praise..." (Excerpt from above.) 2007 - editorial - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonEditorial. (9 June 2007). Head case; can diamonds be an artist’s best friend? [negative take on Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, p. B-6. (Viewed 10 November 2023. S00234).

2007 - comment mentionPresumably Moir, Jan. (13 June 2007). Smiling cats: That’s what our artists should be doing [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull]. The Daily Telegraph (London), p. 19. (Viewed 10 November 2023. S00245). "Oh, aren’t our artists a depressing lot. Tracey Emin has expressed bitchy doubts that all the gems in Damien Hirst’s 50 million diamond skull are real, while David Hockney has expressed doubts about Emin..." (Excerpt from above.)

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Sorid, D. (AP). (14 June 2007). Briefly ["A human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds by British artist Damien Hirst was recently offered for $100 million at a British gallery... "]. Casper Star-Tribune (Wyoming), p. A6. (Viewed 11 November 2023. S00242).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Sorid, D. (AP). (14 June 2007). Briefly ["A human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds by British artist Damien Hirst was recently offered for $100 million at a British gallery... "]. The Citizens’ Voice (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), p. A4. (Viewed 19 November 2023. S00244).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Sorid, D. (AP). (14 June 2007). Briefly ["A human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds by British artist Damien Hirst was recently offered for $100 million at a British gallery... "]. The Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), p. C4. (Viewed 10 November 2023. S00237).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Sorid, D. (AP). (14 June 2007). Briefly ["A human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds by British artist Damien Hirst was recently offered for $100 million at a British gallery... "]. Des Moines Register (Iowa), p. 4D. (Viewed 10 November 2023. S00236).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Sorid, D. (AP). (14 June 2007). Briefly ["A human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds by British artist Damien Hirst was recently offered for $100 million at a British gallery... "]. The Desert Sun (Palm Springs, California), p. E3. (Viewed 19 November 2023. S00243).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Sorid, D. (AP). (14 June 2007). Briefly ["A human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds by British artist Damien Hirst was recently offered for $100 million at a British gallery... "] Independent Record (Helena, Montana), p. 6A. (Viewed 5 November 2023. S00197).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Sorid, D. (AP). (14 June 2007). Briefly ["A human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds by British artist Damien Hirst was recently offered for $100 million at a British gallery... "]. Kenosha News (Kenosha, Wisconsin), p. B7. (Viewed 19 November 2023. S00241).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Sorid, D. (AP). (14 June 2007). Briefly ["A human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds by British artist Damien Hirst was recently offered for $100 million at a British gallery... "]. The Missoulian (Missoula, Montana), presumably p. B4. (Viewed 10 November 2023. S00239).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Sorid, D. (AP). (14 June 2007). Briefly ["A human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds by British artist Damien Hirst was recently offered for $100 million at a British gallery... "] The News and Advance (Lynchburg, Virginia), p. D6. (Viewed 5 November 2023. S00198).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Sorid, D. (AP). (14 June 2007). Briefly ["A human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds by British artist Damien Hirst was recently offered for $100 million at a British gallery... "]. The Oklahoman (Oklahoma City), p. 5B. (Viewed 10 November 2023. S00235).

2007 - news brief - Hirst’s diamond skull at White Cube, LondonPresumably Sorid, D. (AP). (14 June 2007). Briefly ["A human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds by British artist Damien Hirst was recently offered for $100 million at a British gallery... "]. Press of Atlantic City (New Jersey), p. A8. (Viewed 19 November 2023. S00240).

2007 - news brief mentionNilsen, Richard. (17 June 2007). Beauty of the wing [refers to another artwork by Damien Hirst, "a faux stained-glass window made from thousands of butterfly wings", on view at the Phoenix Art Museum— with mention of the diamond skull]. Arizona Republic, p. E1. (Viewed 5 November 2023. S00194).

2007 - article mentionGilbert, Mark (Bloomberg News Columnist). (20 June 2007). How do we know there is a "bubble"? Count the ways [with photo and mention of Damien Hirst’s diamond skull]. St. Petersburg Times, p. 3D. (Viewed 5 November 2023. S00195).

2007 - article mentionSkrypek, Erin. (21 June 2007). Anatomy of a trend; inspired by the human body, designers flesh out new looks [with photo / caption and mention of Damien Hirst’s diamond skull]. Boston Globe, p. E2. (Viewed 5 November 2023. S00196).

2007 - feature article, photo - Hirst’s diamond skull on view at White CubeJames, Clive. (29 June 2007). Why money can’t buy everything [with mention of Damien Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. BBC News. (Viewed 26 September 2021. Q00474). "It’s worth £50m, but Damien Hirst’s skull is nevertheless "art for all". Why? Because it’s glittering, hollow and perfectly brainless - so you can talk about it to anyone, just like you can Paris Hilton..." (Excerpt from above.) 2007 - news brief mentionGilbert, Laurelle. (19 July 2007). Damien Hirst to design for Levi’s... really! [With mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Elle magazine (UK). (Viewed 1 October 2021. Q00569). 2007 - feature article, photo - Hirst’s diamond skull reported to be soldAFP. (30 August 2007). Damien Hirst skull sells for $US100m [with photo of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. ABC News (Australia). (Viewed 4 October 2021. Q00623). 2007 - article mention, photo - Hirst’s diamond skull reported to be soldCohen, David. (30 August 2007). Inside Damien Hirst’s factory [with photo of Hirst and diamond skull, For the love of God]. Evening Standard newspaper (London). (Viewed 1 October 2021. Q00563). "... Yesterday, two months after my meeting with Thompson, a White Cube spokesman revealed that the skull has been bought by an unnamed investment group for cash..." (Excerpt from above.) 2007 - article mentionHawgood, Alex. (Winter 2007). The magnificent seven [with mention: "If Damien Hirst’s $100 million diamond skull blows a hole in your budget, there’s always Guerlain’s one of a kind Diamond KissKiss lipstick... Exclusively at Bergdorf Goodman..."]. New York Times Magazine, p. 26. (Viewed 4 October 2021. Q00608).

2007 - article mentionEgan, Maura. (Holiday 2007; c. December 2007). Performance upstart [on artist Mika Tajima; with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. New York Times Magazine, p. 172. (Viewed 5 October 2021. Q00609). "With Damien Hirst reportedly selling a $100-million diamond-encrusted skull... it’s encouraging to watch the rising career of an artist like Mika Tajima... incorporates many disciplines— performance, architecture, graphic design, sculpture, even fashion— into her art, making for esoteric work that isn’t necessarily an easy sell to the new breed of hedge-fund collectors... " (Excerpt from above.)

2007 - article mentionWallace, Hannah. (Holiday 2007; c. December 2007). The Texas Tate [about the Goss-Michael Foundation; with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. New York Times Magazine, p. 174. (Viewed 10 October 2021. Q00610). "... Over the past decade, Goss and Michael, who commute between London and Dallas, have amassed a collection of mostly British art... Though they tend to buy the work of Y. B. A.’s like... Damien Hirst (it was reported that they considered buying his diamond skull) ..." (Excerpt from above.)

2008 - book mention, photoGray, Simon. (2008). Damien Hirst section [For the love of God listed under "Masterworks", with mention and photo in section]. In Farthing, Stephen (General Editor) 501 Great Artists, pp. 610-12. Barron’s: London. (Viewed 7 November 2021. Q00905). "... For the love of bling; A whole year before the unveiling of For the love of God at his solo exhibition Beyond Belief (2007), Hirst announced to the British media that he was intending to create the world’s most expensive work of art..." (Excerpt from above.)

2008 - spotlighted wire service article, three photos - Hirst’s diamond skull to be on view in AmsterdamReuters Staff (Amsterdam). (26 August 2008). Amsterdam to host Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull [with three photos of Damien Hirst’s For the love of God, one with Hirst]. Reuters. (Viewed 17 September 2021. Q00391). "... the skull will be exhibited at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum for six weeks starting on November 1 before embarking on a world tour, the museum said...." (Excerpt from above.) 2008 - other articlesSee the articles 2008 - spotlighted article, photo - Damien’s diamond skull reported to sell for £50mPreece, R. J. (January / February 2008). Why I love Damien Hirst’s skull [with photo of For the love of God]. Sculpture magazine, 27(1), pp. 42-5. (Viewed 13 September 2021).

2008 - spotlighted interview - Damien’s diamond skull reported to sell for £50mPreece, R. J. (January / February 2008). Damien Hirst: Hype buzz, glamour and art - Interview with Patricia Ellis [accompanied feature article "Why I love Damien Hirst’s skull" listed above.] Sculpture magazine, 27(1), pp. 44-5. (Viewed 17 September 2021).

2008 - article mentionPompeo, Joe. (9 August 2008). Damien Hirst: "I’m a Punk at Heart" [with mention of the Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. The Observer (New York). (Viewed 3 October 2021. Q00600). 2009 articlesSee the articles 2009 - spotlighted article, photos - Damien’s diamond skull at the Rijksmuseum, AmsterdamPreece, R. J. (March 2009). Rock star on tour: Damien Hirst’s skull at the Rijksmuseum [with photo of promotional graphic showing Hirst’s For the love of God on the exterior of the building; and photo of Hirst’s face above the diamond skull]. Sculpture magazine, pp. 14-5. (Viewed 17 September 2021).

2009 - article - Damien’s diamond skull at the Rijksmuseum, AmsterdamPreece, R. J. (1 June 2009). Damien Hirst’s skull at the Rijksmuseum: Behind the scenes. Art Design Publicity at ADC. (Viewed 17 September 2021).

2009 - article mentionGrant, Caroline. (5 September 2009). Teenage graffiti artist accused of stealing "£500,000 box of pencils" in feud with Damien Hirst [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God; with photos of Cartrain with face covered by diamond skull; and a Cartain collage utilizing diamond skull image]. Daily Mail newspaper (UK). (Viewed 10 October 2021. Q00717). "[Cartrain] apparently used the opportunity to take revenge on Hirst, who had reported Cartrain to the Design and Artists Copyright Society after he created a number of collages based on Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull, For The Love Of God... " (Excerpt from above.) 2009 - article mention(2 October 2009). Hirst goes back to the drawing board [with mention of Damien Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. BBC News. (Viewed 4 October 2021. Q00629). "... From the outset 20 years ago, Hirst was always the brilliant ideas man: catch a tiger shark and suspend it in formaldehyde; pin a thousand butterflies to a canvas in the shape of a stain glass window; decorate a real human skull with £14m worth of the finest diamonds. No problem... " (Excerpt from above.) 2009 - photo in article(13 October 2009). Damien Hirst ditches formaldehyde for traditional artwork in a bid to prove that he can actually paint [with photo of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Daily Mail (London). (Viewed 4 October 2021. Q00601). |

| 2010s | c. 2010 - exhibition webpage - Hirst’s diamond skull at Palazzo Vecchio, Florence(c. 2010). Exhibition webpage for For the love of God at Palazzo Vecchio. Città di Firenze (City of Florence, Italy). (Viewed 22 September 2021. Q00422). "... Palazzo Vecchio’s lavishly decorated rooms, which were designed by Vasari, hosted the court of Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici. For the Love of God will be displayed in the Camera of Duca Cosimo... " (Excerpt from above.) 2010 articlesSee the articles 2010 - article mention(13 April 2010). Cab driver given Damien Hirst drawing as tip [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. BBC News. (Viewed 26 September 2021. Q00471). "... The sketch, depicting Hirst’s famous pickled shark and jewelled skull sculptures, is now up for auction... " (Excerpt from above.) 2010 - article, three photos - Hirst’s diamond skull at Palazzo Vecchio, FlorenceBordignon, Elena. (26 November 2010). Damien Hirst; The Palazzo Vecchio in Florence [Firenze] hosts his diamond skull, from November 26th 2010 to 1st May 2011 [with three photos of Hirst’s For the love of God]. Vogue (Italy). (Viewed 29 September 2021. Q00541). 2011 - press release, photo - Hirst’s diamond skull at Palazzo Vecchio, Florence(16 January 2011). Press release: Damien Hirst; For the love of God; Diamond skull by Damien Hirst on view in Florence; At Palazzo Vecchio; 26 November 2010 – 1 May 2011 [with photo of the artwork]. Città di Firenze (via e-flux). (Viewed 22 September 2021. Q00427). 2011 - spotlighted wire service article, photo - Hirst’s diamond skull to be on view at Tate Modern(London). (22 November 2011). Artist Hirst’s diamond skull part of retrospective [with photo of Damien Hirst’s For the love of God and mention of work to be on view in 2012 in Tate Modern, London]. Reuters wire service. (Viewed 13 October 2021. Q00749). 2011 - other articlesSee the articles 2011 - wire service mention - Hirst’s baby diamond skull(London). (9 January 2011). Baby’s skull inspiration for art [with mention of Damien Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. UPI wire service. (Viewed 13 October 2021. Q00748). "... In 2007, Hirst created "For the Love of God," an adult skull covered in diamonds and described as the largest diamond object created since the British crown jewels... " (Excerpt from above.) 2011 - article mention, photoWhite, James. (20 January 2011). Creating a buzz: The Damien Hirst exhibit where thousands of maggots mature into flies... and then feast on abandoned barbecue [with mention and photo of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God, which is not in this Royal Academy of Art, London exhibition]. Daily Mail newspaper. (Viewed 4 October 2021. Q00606). 2011 - article mention, photoJones, Alice. (18 November 2011). The diary: Jack du Rose; Nicholas Lloyd Webber; David Hockney; Russell Kane [with mention and photo of Damien Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. The Independent newspaper (UK). (Viewed 26 September 2021. Q00473). "Five years ago, the jewellery designer Jack du Rose took delivery of a human skull at his studio... The finished object, of course, became For the Love of God, Damien Hirst’s record-breaking work of artwork with the £50m price tag... Now, du Rose is staging his first solo exhibition, which opens next week at Sam Taylor-Wood’s studio in Clerkenwell, east London... " (Excerpt from above.) 2011 - feature article, photo - Hirst’s diamond skull to be exhibited at Tate Modern(21 November 2011). Damien Hirst skull to display in Turbine [with photo of Hirst’s For the love of God]. BBC News. (Viewed 26 September 2021. Q00470). "... The British artist [Hirst], who rejects suggestions his works are a standing joke against the art establishment, first came to public attention with his 1988 Freeze exhibition of his own and fellow students’ work in a disused warehouse in London..." (Excerpt from above.) c. 2012 - exhibition webpage - Damien’s diamond skull at Tate Modern(c. 2012). Exhibition webpage for Damien Hirst. Tate Modern, London. (Viewed 22 September 2021. Q00420). "... To complement the exhibition, Damien Hirst’s diamond-covered skull, For the Love of God 2007, was on show in a purpose-built room in the Turbine Hall. ..." (Excerpt from above.) 2012 - press release - Hirst’s diamond skull at Tate Modern(1 January 2012). Press release: Damien Hirst’s iconic For the Love of God to be shown in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. Tate Modern, London. (Viewed 22 September 2021. Q00430). 2012 - video - Damien Hirst and the diamond skull(11 April 2012). Damien Hirst: For the Love of God; The YBA discusses his iconic diamond-covered skull For the Love of God 2007 [with various scenes of the diamond skull, including at the jewelers, and two shots of media coverage]. 3.01 minutes. Tate website. (Viewed 13 October 2021. Q00750). 2012 - spotlighted wire service article / interview - mentionRiefe, Jordan (Los Angeles). (11 January 2012). A minute with: Damien Hirst on hitting the "spot" [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull; on the occasion of 300 spot paintings on view in 11 international Gagosian galleries]. Reuters. (Viewed 17 September 2021. Q00392). "His ’For the Love of God’ (2007), a skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds which sold for $100 million... [has been derided as a stunt] and heralded as groundbreaking..." (Excerpt from above.) 2012 - other articlesSee the articles 2012 - article mention(3 January 2012). Hockney takes a swipe at Hirst technique [with mention of Damien Hirst’s "diamond-studded skulls"]. BBC News. (Viewed 5 October 2021. Q00631). "... [Hirst] employs up to 100 people in a "factory" that works as a production line for his spot paintings and completes the painstaking work on installations like his diamond-studded skulls... " (Excerpt from above.) 2012 - article mentionSherwin, Adam. (3 January 2012). Hirst’s army of assistants insults art, says Hockney: Veteran’s attack as he joins Order of Merit [with mention of Damien Hirst’s diaond skull, For the love of God]. Daily Mail (London). (Viewed 4 October 2021. Q00607). "David Hockney has criticised Damien Hirst for using an army of assistants to produce the work which is sold solely under his name... Asked by Andrew Marr for Radio Times if this was a veiled criticism of Hirst— famous for covering a human skull with 8,601 diamonds... Hockney nodded and said: ’It’s a little insulting to craftsmen, skilful craftsmen.’ ..." (Excerpt from above.) 2012 - article mention, photo - Hirst’s diamond skull to be on view at Tate Modern(13 March 2012). Tate focuses on Damien Hirst during Olympic summer [with mention and photo of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God, and forthcoming retrospective at Tate Modern]. CBC News (Canada). (Viewed 16 October 2021. Q00762). "... The Hirst exhibit, looking back on two decades of his work, is part of London’s Cultural Olympiad for the 2012 Games..." (Excerpt from above.) 2012 - article mention - Hirst’s diamond skull to be on view at Tate Modern(27 March 2012). Julian Spalding attacks Damien Hirst "con art" [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. BBC News. (Viewed 5 October 2021. Q00632). "... Spalding’s latest book, Con Art— Why You Ought to Sell Your Damien Hirst While You Can— is published next month... [Hirst’s] exhibition opens at Tate Modern on 4 April and runs until 9 September... Hirst’s shark in formaldehyde... will be on display, alongside other famous work including 1990’s A Thousand Years, 1992’s Pharmacy and a £50m diamond-encrusted skull, For the Love of God..." (Excerpt from above.) 2012 - wire service article mention - Hirst’s diamond skull on view at Tate ModernCollett-White, Mike, (2 April 2012). Art is "world’s greatest currency", says Hirst [with mention of Damien Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God on view at Tate Modern]. Reuters. (Viewed 22 September 2021. Q00421). "... There is also the chance to see his diamond-encrusted skull ’For the Love of God’ displayed in a blacked-out box in the cavernous Turbine Hall lit only by spotlights shining on the 8,601 flawless gems set in a platinum cast of a human skull..." (Excerpt from above.) 2012 - article mention - Hirst’s diamond skull on view at Tate Modern(2 April 2012). Damien Hirst says criticism is "to be expected" [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God on view at Tate Modern]. BBC News. (Viewed 26 September 2021. Q00472). "’You’ve got to ignore it,’ he told the BBC’s Will Gompertz... The exhibition features such works as his diamond skull, titled For The Love Of God..." (Excerpt from above.) 2012 - review article - Hirst’s diamond skull at Tate Modern(16 April 2012). Damien Hirst (review, 3 of 5 stars) [with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. TimeOut (London). (Viewed 13 October 2021. Q00751). "Filing past ’For the Love of God’, the diamond skull in its darkened Turbine Hall chamber, as you might a dead royal lying in state, you sense that the camp, funereal nature of Hirst’s art reached a theatrical high point in this 2007 work..." (Excerpt from above.) 2012 - exhibition review - Hirst’s diamond skull at Tate ModernBankowsky, Jack. (Summer 2012). Damien Hirst [retrospective at Tate Modern, exhibition review; with mention of Hirst’s diamond skull, For the love of God]. Artforum. (Viewed 16 October 2021. Q00761). 2012 - feature article, photo on video - Hirst’s diamond skull at Tate Modern(17 September 2012). Damien Hirst is most visited Tate Modern solo show [with mention and photo (on video of TV interview) of Hirst’s diamond skull]. BBC News. (Viewed 4 October 2021. Q00630). "Tate Modern’s Damien Hirst retrospective was the most visited solo show and second-most visited exhibition in the gallery’s history, it has revealed... [The show also featured] his diamond skull, titled For The Love Of God..." (Excerpt from above.) 2013 - exhibition catalogue - Hirst’s diamond skull in ALRIWAQ DOHA show, QatarBonami, Francesco et al. (2013). Damien Hirst: Relics. 303 pp. (Viewed 22 September 2021. Q00429).